Introduction

Every access control discussion eventually lands here.

Someone asks whether RBAC is enough, someone else argues for ABAC, and the room splits between “keep it simple” and “make it adaptive.” On paper, the debate looks theoretical. In production, it’s anything but.

Here’s the reality teams run into: Zero Trust architectures don’t fail because of missing tools. They fail because access decisions stop matching how systems are actually used.

A user logs in from a new device. A contractor accesses a sensitive API after hours.

A trusted employee suddenly triggers a risky behavior pattern.

And yet, the authorization logic underneath often hasn’t changed. It still assumes that roles alone explain intent.

That assumption used to hold. In modern systems, it doesn’t.

This is why ABAC vs RBAC keeps resurfacing not as a philosophical comparison, but as a practical one. Teams are discovering that the access models they relied on for years behave very differently once Zero Trust principles are introduced.

This blog doesn’t argue that one model replaces the other. Instead, it focuses on what actually happens when RBAC and ABAC collide with Zero Trust expectations, where each holds up, and where cracks start to show.

Why Zero Trust Forces a Rethink of Access Control

Zero Trust doesn’t just change how you authenticate. It changes what authorization must do after the login succeeds.

In older models, the strongest checkpoint was the front door: credentials, MFA, maybe VPN. Once inside, access decisions were mostly static. The assumption was simple if the user is authenticated and “in the network,” they’re probably safe.

That’s not how modern systems behave anymore. Users move between SaaS tools, APIs, and cloud services. Devices change. Locations change. Risk changes. Attackers don’t need to break the wall if they can steal a valid identity.

Zero Trust reacts to that reality by treating every access request like a new event that needs a reason. Not a role. Not a title. A reason. The request should be allowed because the user is valid and the context is acceptable and the resource isn’t being accessed in a suspicious way.

This is why access control becomes the real engine behind Zero Trust—because it’s where “verify explicitly” becomes an actual decision, not a slogan.

So when teams compare abac vs rbac, they’re really asking: Can our access model keep up with changing risk and context? Zero Trust expects it to.

RBAC: Why Role-Based Access Control Still Dominates

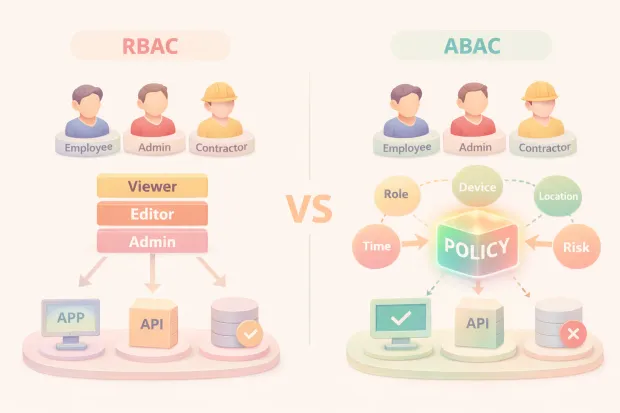

RBAC dominates because it gives teams something they always crave: structure.

With role-based access control, you can map responsibilities to permissions in a clean, explainable way. A support agent gets support permissions. A finance analyst gets finance permissions. An admin gets admin permissions. You can hand this model to auditors, security teams, and engineering teams, and everyone understands it without translation.

This is why RBAC in cybersecurity still remains the default in so many organizations. It’s operationally friendly. It’s easy to manage at the start. It’s predictable. You can build onboarding and offboarding around roles. You can reduce manual entitlement decisions. You can implement RBAC controls using groups, directory roles, and application roles without inventing a policy language.

A realistic role-based access control example is a CRM system:

-

Sales Rep: create/update leads and opportunities

-

Sales Manager: approve discounts and view team pipeline

-

Admin: manage users, integrations, and security settings

That example of role-based access control isn’t exciting, but it’s reliable and reliability is why RBAC keeps winning in day-to-day enterprise reality.

Where RBAC Quietly Starts Failing in Zero Trust

RBAC begins to fail when organizations start needing decisions based on “right now,” not “who you are.”

Roles are stable by design. Zero Trust environments are unstable by nature.

A role doesn’t tell you whether:

-

The device is managed or compromised

-

The location is normal or suspicious

-

The request is happening during expected hours

-

The action is low-risk (read) or high-risk (export, delete, approve)

-

The data is public or regulated

So teams try to force RBAC to behave like ABAC. They add roles for every condition: Contractor-ReadOnly, Contractor-ReadOnly-EU, Contractor-ReadOnly-EU-AfterHours. It looks manageable for a few months, then the role list becomes its own attack surface: unclear, messy, and impossible to maintain cleanly.

This is the trap: RBAC looks simple until it becomes policy by role naming convention. That’s when rbac access stops being clarity and starts becoming accidental complexity.

And the worst part is it happens quietly. You don’t notice it until access reviews become painful, permission drift spreads, and every new use case triggers another role.

ABAC: The Access Model Built for Context

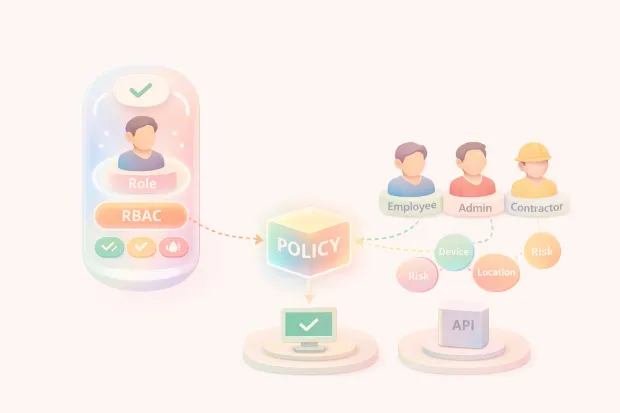

The ABAC model exists because roles can’t explain context.

Attribute-Based Access Control evaluates attributes at runtime about the user, the resource, and the environment, and makes a decision based on policy rules. That sounds complex, but the intent is very practical: allow access when conditions are safe, restrict it when conditions change.

ABAC shines when your access decision depends on signals like:

-

device posture (managed/unmanaged)

-

location (expected/unexpected)

-

time (business hours vs abnormal time)

-

risk score or anomaly detection

-

resource sensitivity (PII, financial data, admin controls)

A simple ABAC-style rule looks like this: A contractor can access the API only if they’re using a managed device, the request comes from an allowed region, and the contract status is active.

That’s why ABAC maps cleanly to Zero Trust: you aren’t granting access “because role.” You’re granting access “because conditions still look safe.”

The Real Trade-off: ABAC vs RBAC in Practice

The real trade-off isn’t “static vs dynamic.” It’s “easy to govern vs easy to scale.”

RBAC is easier to audit and explain. ABAC is easier to adapt when done right.

RBAC breaks through:

-

Role explosion

-

Permission drift (roles slowly becoming junk drawers)

-

Brittle exceptions that don’t generalize

ABAC breaks through:

-

Bad attributes (stale or inaccurate signals)

-

Unclear ownership (who maintains “device compliance”?)

-

Policy sprawl (too many policies with overlapping logic)

-

Debugging pain (why was access denied?)

So ABAC vs. RBAC becomes a question of operational maturity. If your org can’t reliably produce and manage attributes, ABAC can become chaotic. If your org needs context-aware decisions and keeps forcing RBAC to do it, RBAC becomes chaotic.

Different failure paths. Same result: access decisions you can’t trust.

Why Most Zero-Trust Systems End Up Hybrid

Most mature teams don’t replace RBAC. They stabilize RBAC and then layer ABAC on top.

RBAC handles the “base identity” story:

-

Who is this user in the organization?

-

What baseline capabilities come with their job function?

ABAC handles the “situational trust” story:

- Should this user perform this action on this resource right now?

A hybrid model is what makes Zero Trust workable at scale because it keeps the system explainable. You still have roles that define broad access. But you add context-aware enforcement for sensitive actions: exporting data, modifying security settings, accessing privileged endpoints, or touching regulated resources.

The hybrid approach also prevents the worst of both worlds:

-

You avoid role explosion by not encoding context into roles.

-

You avoid ABAC chaos by not encoding job structure into policies.

Governance: The Part Everyone Underestimates

ABAC doesn’t fail because policies are hard. It fails because governance is ignored until production forces the issue.

In ABAC, attributes become security-critical. That means you need answers to questions people avoid early on:

-

Where does each attribute come from?

-

Who owns it?

-

How often is it updated?

-

How do we validate it?

-

What happens if it’s missing?

Even for RBAC, governance matters because role definitions drift over time. “Admin” has five different meanings across systems. “Viewer” starts gaining edit permissions because “it was urgent.”

Governance is the difference between access control being a system and access control being a collection of shortcuts.

If you want Zero Trust to hold, you need policy reviews, attribute lifecycle ownership, and logs that can explain decisions. Otherwise access becomes guesswork with pretty names.

A Subtle Problem That Breaks Authorization Logic

Identity inconsistency breaks authorization more often than teams want to admit.

If a single person can exist as multiple identities email/password one day, social login another day, SSO later your access logic starts evaluating fragments. Roles attach to one identity record. Attributes attach to another. Risk signals apply inconsistently. Access becomes unpredictable.

This is why identity unification matters. Account linking and unified profiles prevent “shadow identities” from silently undermining your authorization model.

In Zero Trust, you can’t continuously evaluate trust if you don’t even know whether two login events belong to the same human.

This seems like an implementation detail. It isn’t. It’s fundamental.

How to Choose Without Overthinking It

You don’t need a philosophy. You need a decision path that matches your reality.

Choose RBAC-first when:

-

your org structure is stable

-

your apps have clear permission boundaries

-

audit clarity is a priority

-

you’re early in access governance maturity

Choose ABAC (or hybrid) when:

-

access depends on device/location/time/risk

-

you protect APIs and microservices

-

you have sensitive actions like exports, admin functions, payments

-

you need step-up enforcement based on context

If you’re serious about Zero Trust, the hybrid model is usually the “adult” choice: RBAC for baseline, ABAC for context. It’s not trendy. It’s simply how systems survive at scale.

Conclusion

Zero Trust doesn’t break because teams misunderstand the concept. It breaks because access decisions lag behind reality.

Roles still matter. They give structure, clarity, and a baseline you can govern. But roles alone can’t explain why a request should be allowed in a moment where context, risk, and behavior change constantly. That’s why the ABAC vs RBAC discussion keeps resurfacing. Not because one model is outdated, but because Zero Trust demands more than static permission mapping.

The strongest systems don’t chase extremes. They use RBAC where stability and clarity are needed, and ABAC where context decides risk. They invest in governance, attribute quality, and identity consistency because authorization is only as strong as the signals it evaluates.

If your access model can’t adapt as quickly as risk does, Zero Trust remains a promise on paper.

If you’re evaluating how RBAC and ABAC fit into your Zero Trust strategy or struggling with role sprawl, inconsistent authorization, or identity fragmentation, it’s worth stepping back and rethinking how access is actually enforced across your stack.

Explore how modern CIAM and authorization platforms support hybrid RBAC + ABAC models designed for Zero Trust, or talk to our identity experts to see what this looks like in your environment.

Because Zero Trust doesn’t succeed at login. It succeeds at every access decision after.

FAQs

Q: What is the main difference between ABAC vs RBAC?

A: The difference between ABAC vs RBAC is how access decisions are made. RBAC grants access based on roles, while ABAC evaluates attributes like user context, device, location, and risk at runtime.

Q: Is RBAC still relevant in Zero Trust security?

A: Yes, RBAC in cybersecurity is still relevant for baseline access and governance. However, Zero Trust environments often require ABAC to handle dynamic, context-aware authorization decisions.

Q: When should organizations use the ABAC model instead of RBAC?

A: The ABAC model works best when access depends on conditions such as device posture, time, or data sensitivity. It’s commonly used in Zero Trust architectures and API-driven environments.

Q: Can RBAC and ABAC be used together?

A: Although both models differ, many organizations combine RBAC controls with ABAC policies. RBAC defines general access, while ABAC adds real-time enforcement based on attributes.