Introduction

Access control problems rarely announce themselves as security failures.

They surface as confusion.

As delays.

As “why does this person still have access?” moments. Someone joins a team and needs access fast. Someone switches roles and keeps their old permissions. Someone leaves, and a few accounts quietly stay active.

This is the mess RBAC was designed to fix.

The benefits of RBAC are rooted in structure. Instead of managing permissions user by user, organizations group access around roles that reflect real responsibilities. That shift alone brings clarity to systems that have grown too fast to manage manually.

For a while, it worked well.

Onboarding becomes predictable. Offboarding becomes safer. Audits stop feeling like forensic investigations.

But here’s the part teams don’t always anticipate.

RBAC assumes that roles are stable, access needs are predictable, and exceptions are rare. Modern systems don’t behave that way. Organizations evolve, products expand, and access decisions become more contextual than static.

That’s where the conversation changes from “What are the benefits of RBAC?” to “Why is this getting harder to manage?”

This blog looks at both sides of RBAC: what it gets right, where it struggles, and why those struggles show up so consistently across growing organizations.

The Benefits of Access Control and Why Structure Becomes Necessary

Access control starts as an annoyance and ends up as a survival mechanism.

Early on, teams move fast because nobody is thinking about boundaries. People share admin access. Permissions get copied from whoever “already has it.” Contractors keep access longer than intended because offboarding is manual and nobody wants to break production.

It works until it doesn’t.

The benefits of access control show up the moment systems and teams stop being small. Once you have multiple apps, multiple environments, multiple departments, and multiple risk levels, access becomes a source of constant friction and silent exposure.

Structure becomes necessary for three reasons.

First, consistency. You can’t secure what you can’t repeat. If access decisions are based on memory or one-off approvals, different managers will grant different access for the same job. That’s how privilege grows unevenly across the organization.

Second, visibility. When leadership asks, “Who can approve payments?” or “Who can export customer data?” the answer shouldn’t require detective work. Access control gives you a way to name those permissions and trace them back to something concrete.

Third, accountability. Without access control, incidents become messy because responsibility is unclear. With access control, access is explicitly granted, explicitly revoked, and explicitly reviewable.

This is the shift: access control stops being about blocking people. It becomes about designing a system where the right access is normal, and everything else is an exception that gets attention.

What RBAC Really Changes Inside an Organization

RBAC doesn’t just change who gets access. It changes how an organization thinks about access.

Without RBAC, access tends to be personal. People get permissions because they asked, because someone trusted them, because they’ve been around long enough, or because “they needed it once.” Over time, that creates identity sprawl where permissions stick to individuals like residue.

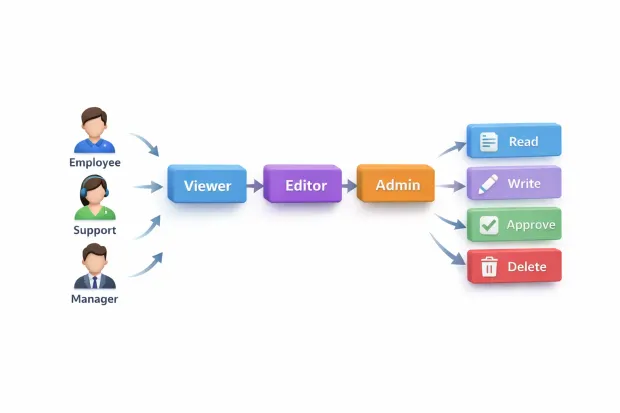

The RBAC model introduces a clean abstraction: roles.

Instead of debating permissions per person, teams define a role based on responsibility and assign people to it. That sounds obvious, but it changes everything operationally.

It changes onboarding.

New employees don’t need custom access decisions every time. Their role assignment becomes the decision. That reduces ramp time and removes the usual back-and-forth approvals that delay productivity.

It changes offboarding.

When access is tied to roles, revoking access is straightforward. Remove the role, and you remove the permission set. In contrast, individual permissions create lingering access because nobody remembers all the places a user was granted access.

It changes audit readiness.

Auditors don’t want a list of users with random permissions. They want to see structure: who holds what responsibility, what that role allows, and how you prevent overreach. Role-based security gives you a model that can be explained and defended without hand-waving.

It also changes cross-team alignment.

This part is underrated. RBAC creates a shared language between security, engineering, and business. Instead of discussing permissions in abstract terms, teams discuss roles that match how work is organized.

That shared language is one of the biggest benefits of RBAC even when teams don’t realize that’s what they’re benefiting from.

But it comes with a trade-off: if roles aren’t governed, they become bloated. If responsibilities aren’t stable, roles become fragile. RBAC improves structure, but it also demands discipline to keep the structure meaningful.

That’s the real change RBAC introduces: it turns access into a system. And systems require ownership.

Role-Based Access Control Models as Systems Mature

RBAC rarely stays static.

As organizations grow, they begin layering rules on top of basic roles. Permissions start inheriting. Some actions are deliberately split to prevent abuse. Sensitive workflows demand separation of duties.

These evolving role-based access control models are responses to real-world pressure, not theoretical design.

They reflect the reality that access control must balance efficiency with restraint. Too loose, and risk increases. Too rigid, and teams slow down.

RBAC models try to walk that line—and often do so successfully, at least initially.

The Benefits of RBAC in Day-to-Day Operations

The strongest benefits of RBAC show up when things change.

New employees can be onboarded quickly without negotiating access from scratch. Departing employees can be offboarded cleanly without chasing lingering permissions. Teams can rotate responsibilities without redesigning access each time.

RBAC also makes access reviews more manageable. Reviewing roles is simpler than reviewing individuals. Patterns emerge. Anomalies stand out.

For organizations dealing with audits, compliance reviews, or regulatory oversight, RBAC offers something critical: a coherent story about access.

That alone keeps it relevant.

Role Explosion: When Structure Turns Into Complexity

Role explosion doesn’t begin as a mistake.

It starts with reasonable exceptions. A slight variation here. A special case there. Each decision makes sense on its own. Collectively, they create sprawl.

Over time, roles multiply faster than anyone can track. Naming conventions become the only differentiator. Teams stop understanding the full impact of assigning a role.

At this point, RBAC loses one of its core advantages: clarity.

Instead of simplifying access, roles begin hiding risk. Removing roles feels dangerous. Creating new ones feels safer than untangling old ones.

That’s how role explosion quietly undermines RBAC systems.

Static Policies in an Environment That Keeps Changing

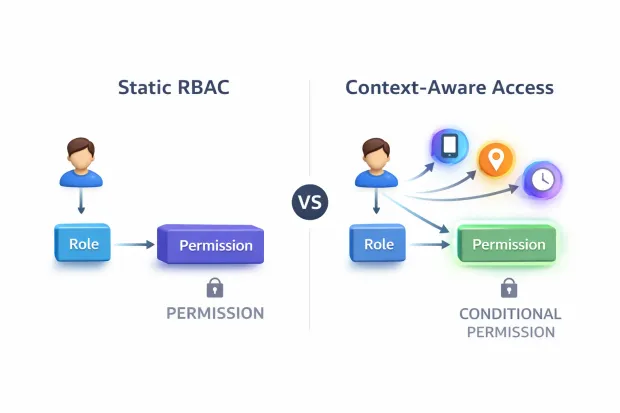

RBAC is built on predictability.

Modern environments are not.

Access decisions increasingly depend on the context where the user is, what device they’re using, when they’re logging in, and what they’re trying to do right now. RBAC doesn’t evaluate those signals. It assumes access can be decided ahead of time.

This mismatch becomes obvious as systems grow more distributed.

Temporary access requests increase. One-off approvals become common. Teams start asking for flexibility RBAC wasn’t designed to provide.

RBAC doesn’t fail here; it simply reaches the edge of what static policies can handle.

Maintenance Overhead: The Cost That Shows Up Later

RBAC often looks deceptively complete after implementation.

But access control isn’t static. People change roles. Teams restructure. Products evolve. Permissions accumulate.

Without regular reviews, RBAC systems drift.

Maintenance overhead doesn’t arrive all at once. It builds quietly through outdated roles, unused permissions, and unclear ownership. Eventually, teams spend more time managing RBAC than benefiting from it.

This isn’t a tooling issue. It’s a governance issue.

RBAC needs caretakers. Without them, it decays.

How RBAC Solutions Support Compliance Requirements

From a compliance perspective, RBAC offers something valuable: traceability.

When implemented properly, RBAC solutions support compliance requirements by showing how access decisions are made, enforced, and reviewed. Roles define boundaries. Permissions are documented. Reviews can be scheduled and proven.

Auditors look for structure and accountability. RBAC provides both—when roles are actively governed.

Without documentation and reviews, RBAC becomes just another assumption. And assumptions don’t survive audits.

RBAC Best Practices That Actually Matter

Most RBAC failures don’t come from bad intentions. They come from treating RBAC like a configuration task instead of an operating model.

Strong rbac best practices start with how roles are defined. Roles should reflect real work patterns, not org charts frozen in time. Job titles change. Responsibilities don’t always. When roles are based on titles alone, access drifts the moment the organization evolves.

Ownership matters more than documentation. Every role needs someone who understands why it exists, what risk it carries, and when it should change. Without clear ownership, roles accumulate permissions quietly. Nobody feels responsible for cleaning them up, and eventually nobody trusts them.

Role creation should be deliberate. When anyone can create roles to solve short-term problems, role explosion becomes inevitable. Mature RBAC systems treat role creation as a controlled action, not a convenience feature.

Reviews are non-negotiable. Not because audits demand them, but because access patterns change even when systems don’t. Periodic access reviews catch permission creep early before it turns into systemic risk.

The best RBAC implementations feel boring. That’s not a flaw. That’s a sign they’re working.

Implementing RBAC Without Creating Long-Term Debt

To implement role based access control well, teams have to resist the urge to design it in isolation.

RBAC should be built around workflows, not abstract permission lists. What does a support agent actually do during a ticket lifecycle? What does an admin do in an incident? What actions carry the most risk? These questions matter more than how many roles exist.

Early RBAC designs often aim for completeness. Mature ones aim for restraint. It’s easier to add permissions later than to take them away once users rely on them. Conservative role design reduces future cleanup.

Constraints should be planned from day one. Separation of duties, approval flows, and escalation paths aren’t optional add-ons—they’re part of how RBAC stays trustworthy as systems scale.

Lifecycle planning is where most teams fall short. Roles need a beginning, a purpose, and an end. When roles outlive their usefulness, they become debt. Without a process to retire or refactor roles, RBAC slowly turns into a liability.

Good RBAC implementations think about the next two years, not just the next release.

When RBAC Alone Isn’t Enough

RBAC was designed for predictability.

Modern systems aren’t predictable.

Access decisions increasingly depend on the context where the user is logging in from, what device they’re using, when the request happens, and how risky the behavior looks at that moment. RBAC doesn’t evaluate those signals. It was never meant to.

This is where teams often misdiagnose the problem. They don’t need to replace RBAC. They need to stop forcing it to solve problems it wasn’t designed for.

Most mature environments treat RBAC as the foundation, not the entire structure. Roles establish baseline access. Contextual controls handle exceptions. Time-bound elevation covers emergencies. Approval workflows protect sensitive actions.

This hybrid approach keeps RBAC relevant without stretching it beyond its limits.

RBAC works best when it’s allowed to do what it does well to provide structure while other mechanisms handle adaptability.

Conclusion

RBAC earns its place for a reason.

The benefits of RBAC clarity, consistency, auditability, and control—solve real problems that every growing system eventually faces. Few access models offer such a clean way to align security, operations, and compliance around a shared structure.

But RBAC doesn’t run on autopilot.

Role explosion doesn’t happen because teams misunderstand RBAC. Static policies don’t fail because RBAC is flawed. Maintenance overhead doesn’t appear because tools are weak.

These issues show up when RBAC is treated as a setup task instead of an ongoing system.

The most effective teams don’t abandon RBAC when it starts to strain. They refine it. They introduce ownership, reviews, constraints, and when needed context-aware extensions that address what RBAC alone can’t handle.

RBAC works best when it’s respected for what it is: a strong foundation, not a complete strategy.

Used thoughtfully, it still provides one of the most practical ways to bring order to access control without sacrificing security or scalability.

FAQs

Q: What are the main benefits of RBAC?

A: The benefits of RBAC include clearer access boundaries, easier onboarding and offboarding, improved audit readiness, and better enforcement of least privilege through role-based security.

Q: What are the biggest limitations of RBAC in real-world systems?

A: RBAC often struggles with role explosion, static access policies, and ongoing maintenance overhead as organizations scale and access needs become more dynamic.

Q: How does RBAC support compliance requirements?

A: RBAC supports compliance by enforcing least privilege, separation of duties, and auditable role-to-permission mappings, provided roles are well-defined and regularly reviewed.

Q: When should organizations move beyond basic RBAC models?

A: Teams often extend RBAC when access depends on context, temporary elevation, or risk signals, combining role-based access control models with attributes or time-bound access controls.