Introduction

Most organizations don’t fail audits because they lack policies. They fail because access quietly drifts out of control.

A contractor gets temporary admin access and keeps it for six months. A support role slowly accumulates privileges “just in case.” A finance system shares logins during quarter-end pressure. None of this feels dramatic at the moment. But when auditors start asking who can access sensitive data and why, data security compliance turns into a scramble.

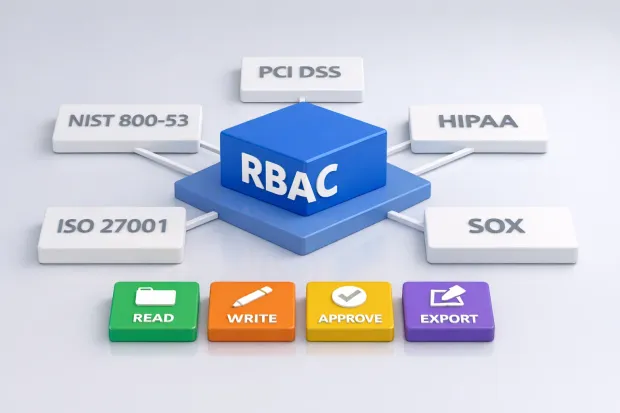

This is why access control keeps showing up in every conversation about security compliance standards. PCI DSS, HIPAA, SOX, ISO 27001, NIST 800-53, they all frame the problem differently, but they circle the same risk: too many people can do too many things, with too little evidence.

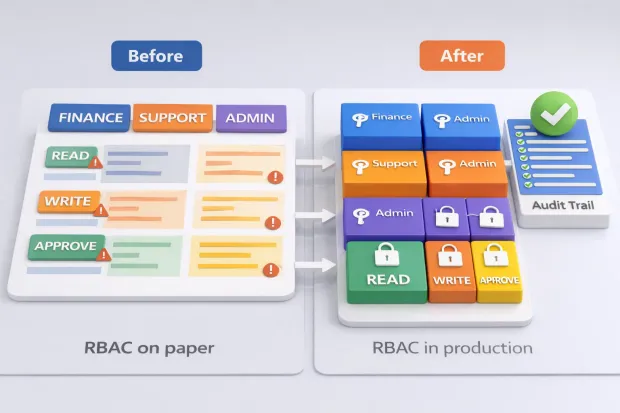

Role-Based Access Control (RBAC) exists to put structure around that chaos. Done right, it becomes a practical way to enforce data compliance regulations, limit blast radius, and prove intent, not just claim it. Done poorly, it turns into a spreadsheet exercise that looks fine on paper and collapses during an audit.

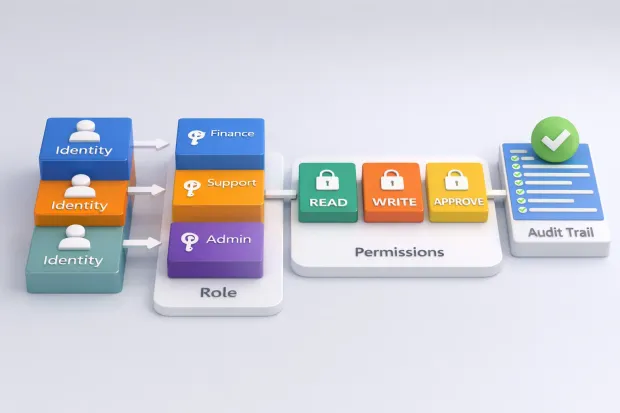

And one quick clarification before we go further: when teams talk about role-based authentication, they’re usually mixing terms. Authentication proves identity. RBAC governs what that identity is allowed to do. Auditors care far more about the second part.

In this guide, we’ll look at how RBAC actually supports modern data compliance standards not in theory, but in the places audits tend to go sideways. We’ll break down how PCI DSS, HIPAA, SOX, ISO 27001, GDPR, and NIST 800-53 all rely on access controls, where RBAC fits cleanly, and where teams usually get it wrong.

Here’s where it gets interesting: the frameworks differ, but the access mistakes repeat.

RBAC Is a Compliance Control

RBAC becomes a compliance control only when it moves beyond intent and starts shaping real system behavior. Policies can describe who should have access, but compliance frameworks care about who actually does and whether that access is constrained, justified, and provable.

This is where many teams blur the line between design and enforcement. They document roles, map them to job titles, and consider the work done. But auditors don’t validate role names. They validate permissions, access paths, and evidence. If a role exists but doesn’t actively restrict actions at the application, API, or data layer, it doesn’t meaningfully support data security compliance.

RBAC works as a compliance mechanism when it enforces least privilege consistently and predictably. Each role must translate into a bounded set of actions, and those actions must be enforced every time a request is made. No side doors. No “temporary” overrides that quietly become permanent. And no ambiguity about what a role actually allows.

Equally important is traceability. Enforcement without visibility still falls short. Compliance teams need to show when access was granted, who approved it, how long it lasted, and what actions were performed. When RBAC is enforced and logged, it becomes one of the clearest ways to demonstrate adherence to modern security compliance standards without relying on explanations or exceptions.

Why Every Major Compliance Framework Keeps Pointing Back to Access Control

Compliance frameworks vary in structure, terminology, and scope, but they converge on a shared concern: controlling who can access sensitive systems and data, under what conditions, and with what level of oversight. This convergence isn’t accidental. Access is where policy meets risk.

Whether a framework is focused on payment data, health records, financial reporting, or enterprise security posture, the underlying assumption is the same. Unauthorized or excessive access is one of the fastest paths to data exposure, fraud, or regulatory violation.

That’s why access control shows up repeatedly across data compliance standards, even when it’s framed differently.

RBAC fits naturally into this pattern because it provides structure. It creates a repeatable way to align permissions with responsibilities. More importantly, it creates boundaries that can be reviewed, tested, and audited.

Frameworks don’t require organizations to use RBAC by name, but they require outcomes least privilege, separation of duties, access reviews, and accountability that RBAC is well suited to deliver.

What often gets missed is that access control isn’t a one-time requirement. Frameworks expect it to evolve as roles change, systems expand, and risk profiles shift. RBAC supports this evolution when roles are designed as living controls, not static artifacts. That’s why it remains a foundational element across data compliance regulations, even as technical environments become more complex.

PCI DSS and RBAC: “Business Need to Know” in Practice

PCI DSS frames access control around a deceptively simple idea: access to cardholder data should be limited to individuals whose job requires it. That “business need to know” language sounds straightforward, but enforcing it consistently is where organizations struggle.

RBAC provides a practical way to operationalize this requirement. Instead of granting broad access to systems that touch payment data, roles can be defined around specific operational responsibilities.

Support teams, finance staff, developers, and infrastructure operators each receive access aligned to what they actually need to perform their function.

This becomes especially important as environments grow. Payment workflows often span multiple systems, APIs, and services. Without enforced role boundaries, access spreads organically, and PCI scope expands with it.

RBAC helps contain that sprawl by ensuring access to cardholder data environments remains deliberate and traceable.

From a compliance standpoint, RBAC also simplifies evidence collection. Auditors don’t just want to know that access is restricted, they want to see how restrictions are applied and reviewed. When roles are clearly defined, enforced, and periodically reviewed, organizations can demonstrate alignment with PCI DSS expectations without relying on manual explanations or exceptions.

HIPAA and RBAC: Minimum Necessary Is an Access Problem

HIPAA’s “minimum necessary” standard is often discussed as a policy obligation, but in practice, it’s an access control challenge. Limiting exposure to electronic protected health information requires more than awareness; it requires technical enforcement.

RBAC supports this by translating abstract safeguards into concrete permissions. Roles can be aligned to clinical, administrative, and operational responsibilities, ensuring individuals can access only the information required for their function. This reduces accidental exposure and limits the impact of compromised credentials.

HIPAA also emphasizes accountability. Unique user identification, access monitoring, and audit trails are all part of the expectation. RBAC strengthens these safeguards by creating clear associations between users, roles, and actions.

When access decisions are role-driven and logged, it becomes easier to investigate incidents and demonstrate compliance.

What often undermines HIPAA programs is over-broad access granted for convenience or speed. RBAC counters this by forcing access decisions to be intentional. It doesn’t slow care delivery when implemented correctly but it does make excessive access harder to justify.

And from a data security compliance perspective, that discipline matters far more than policy language alone.

SOX and RBAC: Preventing Financial Access From Getting Creative

SOX compliance is less about security theater and more about control discipline. Its core concern is whether access to financial systems can alter records, approvals, or reporting in ways that undermine trust in financial statements.

When access boundaries are loose, even well-intentioned teams introduce risk without realizing it.

RBAC plays a critical role here by enforcing separation of duties in systems that handle accounting, reporting, and financial operations. Roles define who can initiate transactions, who can approve them, and who can modify underlying data.

When those responsibilities blur, auditors start asking uncomfortable questions not because fraud has occurred, but because it could.

What makes SOX particularly sensitive to access control is traceability. It’s not enough to restrict access; organizations must show that access was appropriate at the time it was granted and reviewed regularly afterward. RBAC supports this by creating a stable structure auditors can evaluate over time, rather than a constantly shifting set of ad-hoc permissions.

Without enforced RBAC, financial access tends to expand quietly. Emergency privileges linger. Admin rights get reused. Ownership changes but access does not.

SOX audits don’t fail on intent; they fail when access history can’t be explained cleanly. RBAC reduces that ambiguity by making access deliberate, reviewable, and defensible.

ISO 27001, GDPR, and RBAC: Where Identity Becomes Auditable

ISO 27001 formalizes something many organizations already know intuitively: security controls need to be repeatable, measurable, and auditable. Access control sits squarely in that expectation, particularly in how identities are managed and permissions are granted, reviewed, and revoked.

RBAC aligns well with ISO 27001 because it turns access decisions into structured controls. Roles become a documented mechanism for enforcing least privilege, and identity lifecycle events onboarding, role changes, offboarding become auditable processes instead of informal handoffs.

This is where identity management stops being operational plumbing and starts becoming governance.

GDPR intersects here, but it’s often misunderstood. Achieving iso 27001 gdpr compliance doesn’t mean RBAC alone satisfies GDPR requirements. GDPR focuses on lawful processing, data minimization, and individual rights.

RBAC supports these goals indirectly by limiting who can access personal data and reducing accidental exposure.

From a gdpr compliance framework perspective, RBAC reduces risk surface area. Fewer people can access sensitive data, access is tied to defined responsibilities, and misuse becomes easier to detect.

For auditors and regulators, this combination of structured roles, enforced access, and documented reviews turns identity from an abstract concept into something that can actually be examined.

NIST 800-53 and RBAC: When Controls Meet Enforcement

NIST 800-53 is often described as comprehensive, but its strength lies in how explicitly it ties security principles to control outcomes. Access control requirements aren’t aspirational; they're meant to be implemented, measured, and verified.

RBAC fits naturally into this model because it provides a concrete way to enforce least privilege and role separation across systems. Controls related to access authorization, privilege management, and accountability depend on more than policy statements.

They depend on mechanisms that consistently enforce decisions at runtime.

What makes NIST particularly relevant is its emphasis on enforcement over documentation. A control that exists only in writing doesn’t satisfy expectations. RBAC must actively govern access requests, limit actions based on role context, and record those decisions.

This is where RBAC shifts from being an architectural pattern to an operational control.

As organizations align with security compliance standards built on NIST guidance, RBAC becomes a bridge between control catalogs and real systems. It ensures that access rules aren’t just defined once but applied continuously.

When controls meet enforcement, audits become validation exercises instead of discovery missions and RBAC is often what makes that possible.

One RBAC Model, Many Frameworks: The Mapping Layer

Compliance becomes unnecessarily complex when access controls are designed separately for every framework. PCI DSS, HIPAA, SOX, ISO 27001, and NIST 800-53 may use different languages, but they are evaluating the same underlying behaviors: who can access sensitive systems, how that access is justified, and whether it is reviewed and controlled over time.

The mapping layer is where RBAC proves its value across data compliance standards. A single RBAC model built around clearly defined roles, scoped permissions, and enforced boundaries can support multiple frameworks simultaneously.

What changes from one audit to another is not the access model itself, but how its evidence is presented.

Roles and permissions map cleanly to different expectations. Least privilege aligns with NIST and ISO controls. Separation of duties supports SOX. Restricted access to sensitive data satisfies PCI DSS and HIPAA requirements.

Logging and review cadence reinforce data security compliance across all of them. The same control surface, viewed through different regulatory lenses.

This is where teams often overcomplicate things. Instead of creating parallel compliance structures, the mapping layer allows organizations to translate one enforced RBAC system into framework-specific narratives.

Auditors don’t need custom controls, they need clarity. RBAC provides a common control language that makes that clarity possible.

RBAC Implementation That Holds Up in an Audit

RBAC implementation becomes audit-worthy only when it reflects how systems actually behave in production. Auditors aren’t interested in idealized role diagrams or policy statements. They want to understand how access decisions are made, enforced, and reviewed in real time.

Strong rbac implementation starts by treating permissions as the foundation. Roles are simply containers that bundle those permissions according to responsibility. When roles are built first and permissions are guessed later, access tends to sprawl.

When permissions are defined deliberately and roles are assembled from them, access remains predictable.

Enforcement is the critical line between theory and compliance. RBAC must be applied consistently at the points where access matters to applications, APIs, data layers not just in user interfaces.

If a role restricts actions in one place but not another, auditors will notice the inconsistency quickly.

Equally important is lifecycle control. Access must change when people change roles, leave teams, or exit the organization. Reviews need to be routine, approvals traceable, and exceptions time-bound.

When RBAC is implemented as a living system rather than a static design, it becomes one of the most defensible controls under modern security compliance standards.

Here’s Where Teams Usually Go Wrong With RBAC

Most RBAC failures don’t come from bad intent. They come from shortcuts that feel harmless at the time. Roles get overloaded to avoid friction. Admin access becomes a convenience tool. Temporary permissions quietly become permanent.

One common issue is treating RBAC as a user-interface feature instead of a system-level control. Roles may limit what users see on screen, but backend services still accept unrestricted requests.

From a compliance perspective, that gap is indefensible. Access control that doesn’t apply everywhere access is possible doesn’t really exist.

Another frequent problem is neglecting review and ownership. Roles are created, but no one is accountable for maintaining them. Permissions accumulate. Teams change. Access stays the same.

Over time, the RBAC model stops reflecting reality, and audits turn into discovery exercises rather than validation.

There’s also confusion between authentication and authorization. Teams talk about role-based authentication when the real issue is permission enforcement. Strong login controls don’t compensate for excessive access once someone is inside.

RBAC works best when it’s boring, disciplined, and slightly strict. When teams resist that discipline, access becomes opaque, and compliance gaps follow quickly.

Conclusion

Compliance frameworks change. Access problems don’t.

Whether you’re dealing with PCI DSS scoping questions, HIPAA safeguards, SOX access reviews, or ISO 27001 audits, the same patterns keep surfacing. Too many roles. Too much privilege. Not enough evidence. And no clean way to explain why someone had access in the first place.

This is where solid RBAC implementation quietly does its job. It turns abstract policy language into enforceable boundaries. It makes data security compliance something you can demonstrate, not defend. And it gives auditors what they’re really looking for: clarity.

RBAC doesn’t replace your gdpr compliance framework, and it won’t magically satisfy every requirement in complex data compliance regulations. But it reduces exposure by narrowing access, enforcing least privilege, and leaving a trail that shows decisions were intentional, not accidental.

The teams that struggle with compliance aren’t usually missing controls. They’re missing discipline. Roles that mean something. Permissions that are scoped. Reviews that happen on schedule. Logs that tell a complete story.

When access stops being a mystery, compliance stops feeling like a fire drill. It becomes a system predictable, defensible, and far easier to live with.

And that’s the real value of RBAC across today’s security compliance standards: not passing audits faster, but failing them less often.

FAQs

Q: Is RBAC required for compliance with security regulations?

A: RBAC isn’t always named explicitly, but its outcomes, least privilege, access control, and accountability, are required across most security compliance standards. RBAC is one of the most practical ways to meet those expectations consistently.

Q: How does RBAC support data security compliance across multiple frameworks?

A: RBAC limits access based on responsibility, enforces separation of duties, and creates audit-ready evidence. That same access structure can be mapped to PCI DSS, HIPAA, SOX, ISO 27001, and NIST requirements.

Q: Does RBAC help with GDPR compliance?

A: RBAC doesn’t replace a GDPR compliance framework, but it significantly reduces risk. By limiting who can access personal data and logging those actions, RBAC supports data minimization and accountability principles.

Q: What breaks RBAC during audits?

A: RBAC usually fails when roles aren’t enforced everywhere, reviews are skipped, or permissions quietly accumulate. Auditors focus less on role names and more on whether access decisions are consistent and provable.